Optical Kagome Lattice

Optical Kagome Lattice

We are building an experiment to study quantum many-body physics in the Kagome lattice.

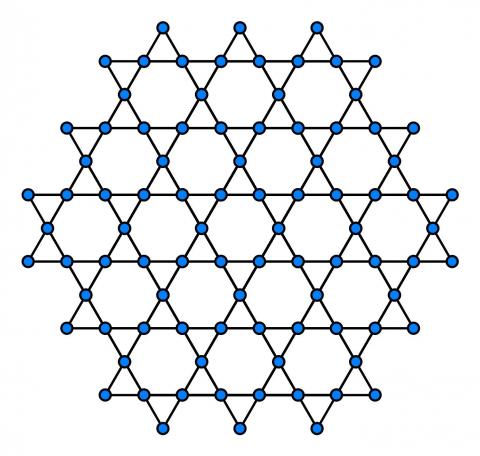

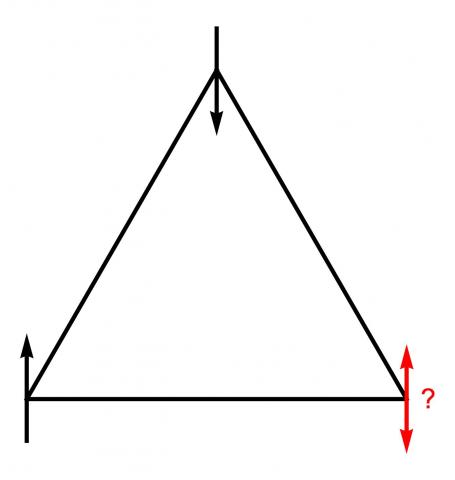

The Kagome lattice consists of corner-sharing triangles and is characterised by a large degree of geometric frustration, which becomes visible for instance in an antiferromagnetic Heisenberg model: while two of the three spins can be antiparallel, the third one is frustrated—both possible configurations will always contain one good and bad bond and are hence degenerate. This results in a macroscopic degeneracy of configurations which can host new physics. This type of system is expected to form a spin liquid, where the spin distribution does not order even at zero temperature. Quantum spin liquids are predicted to have fractionalised excitations, i.e. they form quasiparticles which have an effective spin or charge that is smaller than that of their constituents [1]. They are also thought to capture many of the essential features of high-temperature superconductors [2].

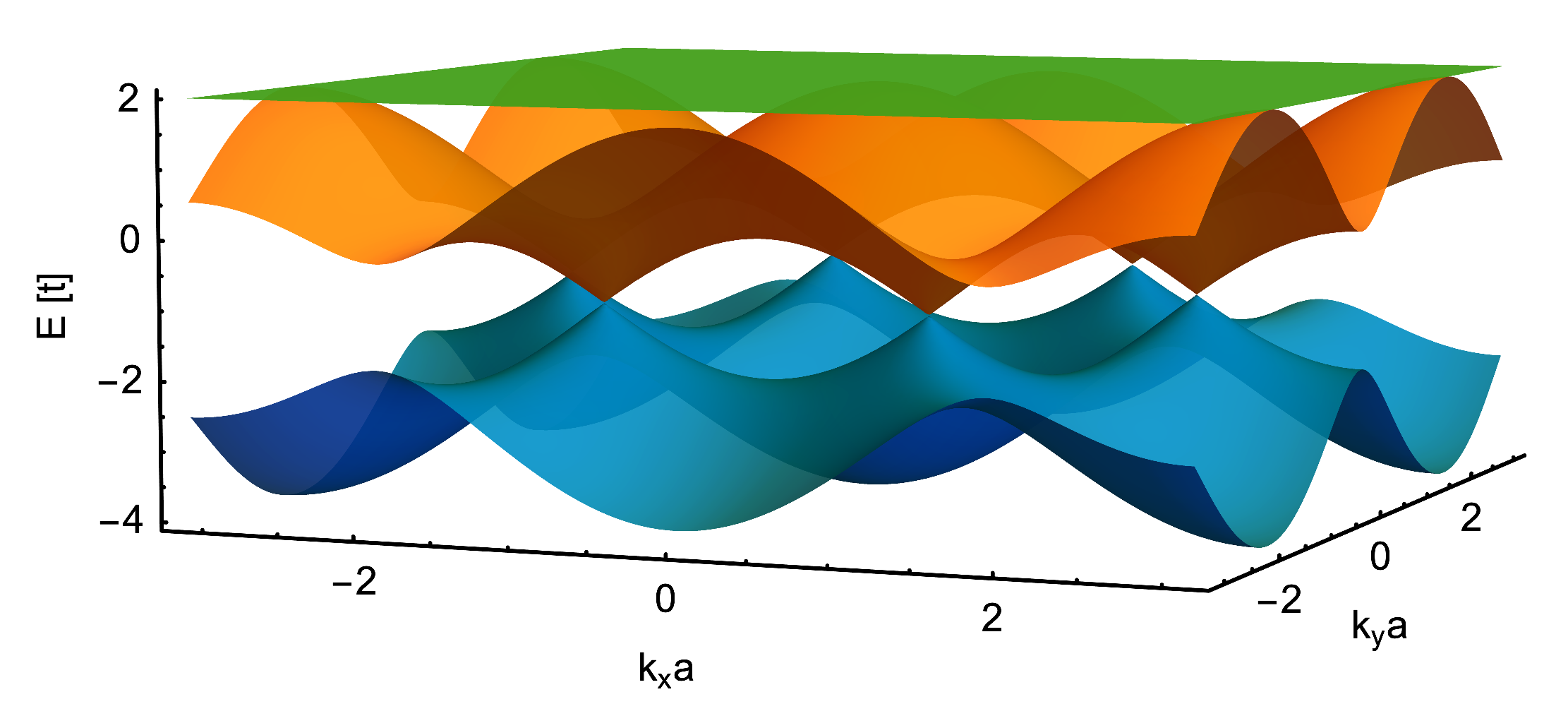

For single particles, this geometrical frustration can lead to the appearance of a flat band. The lowest motional band of the Kagome lattice is split into three subbands and in the tight-binding limit (i.e. when the lattice is sufficiently deep), the uppermost subband is flat. The normal velocity of particles in a lattice, e.g. electrons in an ionic lattice or ultracold atoms in an optical lattice, is proportional to the curvature of the band they occupy. Atoms in a flat band therefore do not have kinetic energy and are inherently strongly correlated, i.e. their transport behaviour is determined entirely by interactions and topology.

One of the major challenges of this experiment will be to stabilise the atomic cloud in the flat motional band, which is the uppermost of three in the tight-binding approximation. However, ultracold atoms naturally occupy the lowest energy states, which are in the bands that exhibit the Dirac cones. In order to invert the population, such that the flat band is predominantly occupied, we will put the atomic cloud into a negative temperature state. As shown in experiments by Braun et al. [3], being able to tune the interaction strength between particles from repulsive to attractive during an experimental sequence is the key to achieving a stable negative temperature state.

We will cool bosonic 87Rb and 39K and fermionic 40K to ultracold temperatures and trap them in an optical lattice formed by lasers.

Currently, we can cool and trap 87Rb, 39K and 40K in our magneto-optical trap (MOT) and are able to produce Bose-Einstein condensates of 87Rb and 39K. Next steps include cooling 40K to quantum degeneracy and implementing the optical lattice.

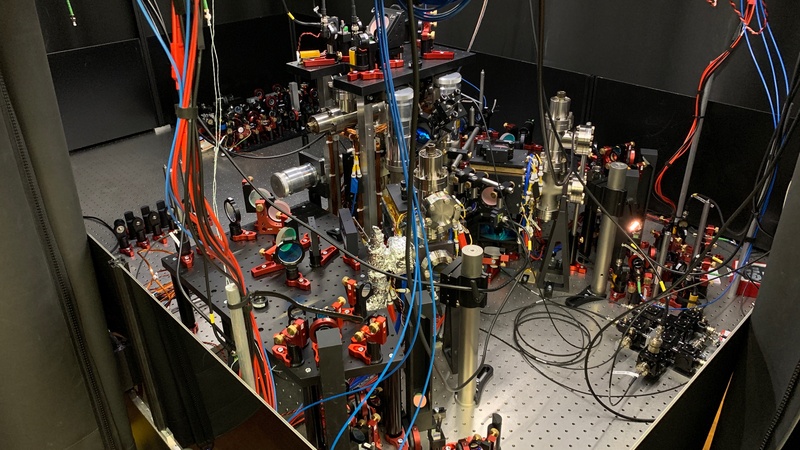

Red Table: Here we prepare lasers for the cooling and trapping of our three atomic species.

Experiment Table: This is where our vacuum chamber sits and the experiments are performed.

[1] T.-H. Han et al., Nature 492, 406–410 (2012)